11:45 AM | ***Get ready…cold, stormy pattern getting locked in…weekend major storm threat in transition to some very cold air***

Paul Dorian

06Z GEFS forecast map of 850 mb temperature anomalies averaged over 5-day periods with days 12-16 (right); courtesy NOAA/EMC, tropicaltidbits.com

Overview

As we approach the middle part of January, it is time for a mid-winter review and many of the players on the field suggest a cold and stormy pattern is setting up for the central and eastern US and it could last well into February – perhaps even into March. Two of the big players on the field include a weak-to-moderate “Modoki” El Nino in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and a blob of warmer-than-normal water in the northeast Pacific. In addition, there has been a significant stratospheric warming event in recent weeks that will also play a role in the change to sustained colder-than-normal weather in coming weeks for much of the eastern half of the nation. Finally, low solar activity has been well-correlated with “high-latitude blocking” and that appears to be part of the overall pattern change in coming weeks. This unfolding cold and stormy weather pattern could very well include some extreme cold and the transition this upcoming weekend to some very cold air - the coldest so far this season - looks like it may be accompanied by a major storm along the eastern seaboard with significant rain, ice and/or snow.

Discussion

There was an unusually early snowstorm this winter season during the month of November that hit the Philly-to-NYC corridor quite hard and even impacted the DC metro region. Another snowstorm took place in December that resulted in significant snow just south of DC in, for example, the region between Charlottesville, VA and Richmond, VA. Both of these snowstorms turned out to be rather isolated snow events. In fact, temperatures following the December snow event in the Mid-Atlantic region were generally above-normal for the next three or four weeks. This past weekend’s snowfall; however, which pounded the DC metro region with 10+ inches is likely not going to be an isolated event. Rather, it just may be the opening act in what appears to be an upcoming sustained cold and stormy weather pattern. Several factors support the notion of a wild ride coming for the central and eastern US in coming weeks and they are discussed below.

Current sea surface temperature anomalies with a “Modoki” type of El Nino in the central Pacific (circled area) and a large area of the northeastern Pacific (circled area) that is warmer-than-normal. Map courtesy CMC Environment Canada

Pacific Ocean sea surface temperature anomalies

The Pacific Ocean is the planets biggest, covers more than 30 percent of the Earth’s surface, and is larger than the landmass of all the continents combined. As such, its sea surface temperature (SST) pattern has a tremendous influence on all weather and climate around the world. This winter season there are two important areas of interest and both will play a role in this stretch of cold and stormy weather for the central and eastern US. The first area of interest is associated with a “Modoki” or centrally-based El Nino with warmer-than-normal waters in the middle of the equatorial Pacific and the second area is a large blob of warmer-than-normal water in the northeastern Pacific just to the south of Alaska.

As far as El Nino is concerned, not only is the magnitude important in terms of its potential impact on wintertime temperatures in the US, but the specific location can be quite crucial as well. Currently, there is a weak-to-moderate El Nino based in the central part of the Pacific Ocean. The (limited) strength and specific location of this El Nino has been often correlated with colder-than-normal and snowier-than-normal winters for the central and eastern US and this oceanic set up should last through the remaining part of the winter season. A centrally-based El Nino tends to activate the southern branch of the jet stream as it results in boosted water vapor that is released into the atmosphere and the warmer-than-normal sea surface temperatures tend to destabilize the lower part of the atmosphere as well. An activated southern branch of the jet stream, in turn, raises the chances for a storm track across the southern states and the eastern seaboard - generally more favorable for snow in places like the big cities of the I-95 corridor - as long as there is sustainable cold air.

In addition to the "centrally-based" El Nino, there is another important region which too is signaling for numerous cold air outbreaks into the eastern and southern US. Specifically, very warm water currently in the northeastern part of the Pacific Ocean should act to “pump up” an upper-atmosphere ridge along the west coast of North America and this, in turn, usually allows for the penetration of cold air from northern Canada into the central and eastern US.

A 30-day loop of temperature anomalies at the 10-millibar level with significant stratospheric warming (red, orange) at high-latitudes; courtesy NOAA

Stratospheric warming

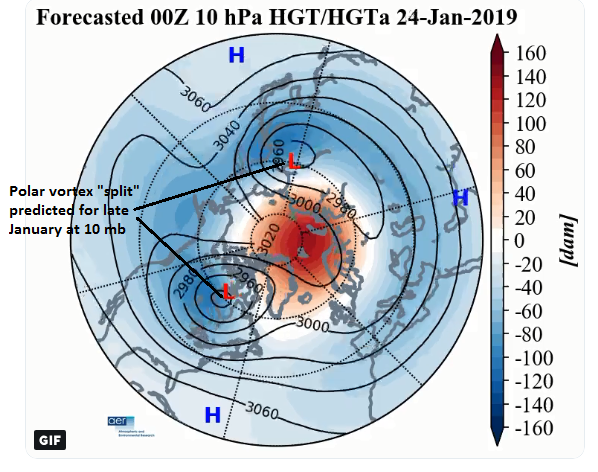

One of the ways to monitor the potential for wintertime Arctic air outbreaks in the central and eastern U.S. is to follow what is happening in the stratosphere over the Northern Hemisphere. Sudden Stratospheric Warmings (SSWs) are large, rapid temperature rises in the winter polar stratosphere, occurring primarily in the Northern Hemisphere, and these events have been found to set off a chain of events in the atmosphere that ultimately can lead to polar vortex disruptions and Arctic air outbreaks for the central and eastern US. Indeed, a significant stratospheric warming event began in early December causing a “splitting” of the polar vortex into smaller pieces around the world and this raises the chances for frigid weather here in coming weeks.

Stratospheric temperatures at high-latitudes featured a sharp spike during the month of December (far right); courtesy NOAA

During the winter months in the polar stratosphere, temperatures are typically lower than minus 70°C. The cold temperatures are combined with strong westerly winds that form the southern boundary of the stratospheric polar vortex which plays a major role in determining how much Arctic air spills southward toward the mid-latitudes. This dominant structure is sometimes disrupted in some winters by being displaced, split apart or even reversed. Under these circumstances, the winds can decrease or change directions and the temperatures in the lower stratosphere can rise by more than 50°C in just a few days. Indeed, in this particular SSW event that began in December 2018, the temperatures spiked in polar regions at the 10 millibar level in just a few days from around -65°C to -35°C.

10-day forecast map (January 24) for 500 mb heights/anomalies features a ‘split” polar vortex; map courtesy AER, Inc. (Judah Cohen), NOAA

In response to the stratospheric warming (and associated layer expansion) at the high latitudes, the troposphere cools down dramatically (with layer contraction) at the high latitudes. This tropospheric cold air can then be transported from the high latitudes to the middle latitudes given the right overall weather pattern (e.g., "high-latitude blocking" over Greenland/northern Canada). The tropospheric response to the SSWs closely resembles the negative phase of the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), involving an equatorward shift of the North Atlantic storm track; extreme cold air outbreaks in parts of North America, northern Eurasia and Siberia; and strong warming of Greenland, eastern Canada, and southern Eurasia (Thompson et al., 2002). The entire process from the initial warming of the stratospheric at high latitudes to the cooling in the troposphere at middle latitudes can take several weeks to unfold. In fact, it is not at all unusual for an extended significant warm up to take place before the “stratospheric warming induced” cool down takes hold (e.g., December 1984 (warm), January 1985 (cold)).

Extreme cold on the table

Some stratospheric warming events in recent history have, in fact, been followed by widespread extreme cold air outbreaks across the central and eastern US - usually several weeks after the initial upper atmosphere warming. Sometimes, the initial response with extreme cold can take place on one side of the North Pole before it breaks out on the other side. Last week featured some unusual cold and snow for parts of Europe and its been quite cold in Asia as well.

One example of extreme cold that took place following a major SSW event occurred in January 1985. That winter season, a major SSW event began in the month of December which actually ended warmer-than-normal for much of the eastern US), but then changed dramatically to extremely cold conditions by later in January 1985 – some several weeks after the SSW event began. In fact, it turned out to be so cold for Ronald Reagan’s second inauguration on January 20th, 1985 that all outdoor activities for that day were moved inside to protect the public. Interestingly, the month of December in 1984 actually was warmer-than-normal in much of the eastern half of the nation (and much of this December was warmer-than-normal in the eastern US).

12Z GEFS (left) and 12Z EPS (right) forecast maps of 500 mb height anomalies for late January both feature deep troughs over the eastern US and Aleutian Islands of Alaska (in blue, purple), strong ridging along the west coast of Canada/US (in orange, red), and “high-latitude blocking” over Greenland and other nearby polar regions (in orange, red)…a snow lovers delight to see this type of pattern; maps courtesy NOAA/EMC, WSI, Inc.

Low solar activity and its impact on “high-latitude blocking”

The sun is blank today and has been for the past 7 days and will likely be for much of 2019 as we are approaching a deep solar minimum. Empirical observations have shown that the sun can have important ramifications on weather and climate on time scales associated with the average solar cycle (i.e., 11-years). For example, there is evidence that low solar activity years tend to be correlated with more frequent “high-latitude blocking” events (see Winter Outlook). “High-latitude blocking” during the winter season is characterized by persistent high pressure in northern latitude areas such as Greenland, northeastern Canada, and Iceland. Without this type of blocking pattern, it is quite difficult to get sustained cold air outbreaks in the central and eastern US during the winter season and that is usually a critical requirement for snowstorms in, for example, the big cities of the I-95 corridor. The latest computer forecast models support the notion of “high-latitude blocking” in coming weeks which may play a role in the upcoming cold and stormy weather pattern for the central and eastern US.

06Z GEFS forecast maps of 850 mb temperature anomalies averaged over 5-day periods with days 7-11 (left) and days 12-16 (right); courtesy NOAA/EMC, tropicaltidbits.com

Weekend storm threat as we transition to some very cold air

This week will generally feature moderate cold and there is a system to monitor for Thursday night. Low pressure could bring some snow and/or rain to the Mid-Atlantic region on Thursday night with temperatures only marginally cold. A transition this weekend to some bitter cold air could result in a major precipitation event along the eastern seaboard with significant amounts of rain, ice and/or snow on the table.

12Z GFS surface forecast map for Sunday morning, January 20th, with snow (in blue) across much of the interior Northeast US and rain (in green) along coastal regions; map courtesy NOAA/EMC, tropicaltidbits.com

It is too early to break down the totals of each precipitation type, but a rain-to-ice-to-accumulating snow is a possibility. Following the weekend storm, bitter cold air is likely to flood the Mid-Atlantic region by the early part of next week – the coldest air of the winter season so far.

Get ready…it’s gonna be a wild ride!

Meteorologist Paul Dorian

Perspecta, Inc.

perspectaweather.com

Video discussion: