7:15 AM | *The Great New England Hurricane of 1938*

Paul Dorian

Photo of Battery Park (Manhattan, NY) during 1938 storm (courtesy National Weather Service)

Overview

On September 21, 1938, one of the most destructive and powerful hurricanes in recorded history struck Long Island and Southern New England. It was the first major hurricane to strike New England since the year 1869. The storm developed near the Cape Verde Islands on September 9, tracking across the Atlantic and up the Eastern Seaboard. The storm hit Long Island and Southern Connecticut on September 21, moving at a forward speed of 47 mph! Tomorrow marks the 81st anniversary of storm known as "The Great New England Hurricane of 1938" as well as "The Long Island Express" and the "Yankee Clipper". With no warning, the powerful category 3 hurricane (previously a category 5) slammed into Long Island and southern New England causing approximately 682 deaths and massive devastation to coastal cities and became the most destructive storm to strike the region in the 20th century. Little media attention was given to the powerful hurricane while it was out at sea as Europe was on the brink of war and the overriding story of the time. There was no advanced meteorological technology such as radar or satellite imagery to warn of the storm’s approach.

9AM surface weather map of 1938 hurricane on September 21st; courtesy NOAA/NWS central library data imaging project

Genesis of the great storm

The storm began on September 9th near the Cape Verde Islands in the eastern Atlantic. About a week later, the captain of a Brazilian freighter sighted the storm near Puerto Rico and radioed a warning to the US Weather Bureau and it was expected that the storm would make landfall in south Florida where preparations frantically began. By September 19th, however, the storm suddenly changed direction and began moving north, parallel to the eastern seaboard. It had been many decades since New England had been hit by a substantial hurricane and few believed it could happen again. The storm picked up tremendous speed as it moved to the north following a track over the warm Gulf waters.

Track data courtesy of the NOAA National Hurricane Center: Hurricane Research Division: Re-analysis Project

Devastation arrives on September 21st

By the time the fast-moving storm approached Long Island, it was simply too late for a warning. In the middle of the afternoon on September 21st, the hurricane made landfall along the south shore of Long Island right around high tide when there was nearly a new moon (highest astronomical tide of the year). To make matters worse, this part of the country had just been through a long rainy period which saturated grounds before the arrival of this great storm. Waves as high as 40+ feet swallowed up coastal homes and homes that survived the storm surge succumbed to the damaging winds that reached 111-129 mph (lower to the west and higher to the east). By late afternoon, the hurricane raced northward at an amazing speed of nearly 50 mph crossing the Long Island Sound and reaching Connecticut (Landsea et al. 2013, National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division Re-Analysis Project). The storm surge of 14-18 feet above normal tide level inundated parts of Long Island and later the southern New England coastline. The waters in Providence harbor rapidly submerged the downtown area of Rhode Island’s capital under more than 13 feet of water and many people were swept away. The accelerating hurricane then continued northward at tremendous speed across Massachusetts generating great flooding in its path.

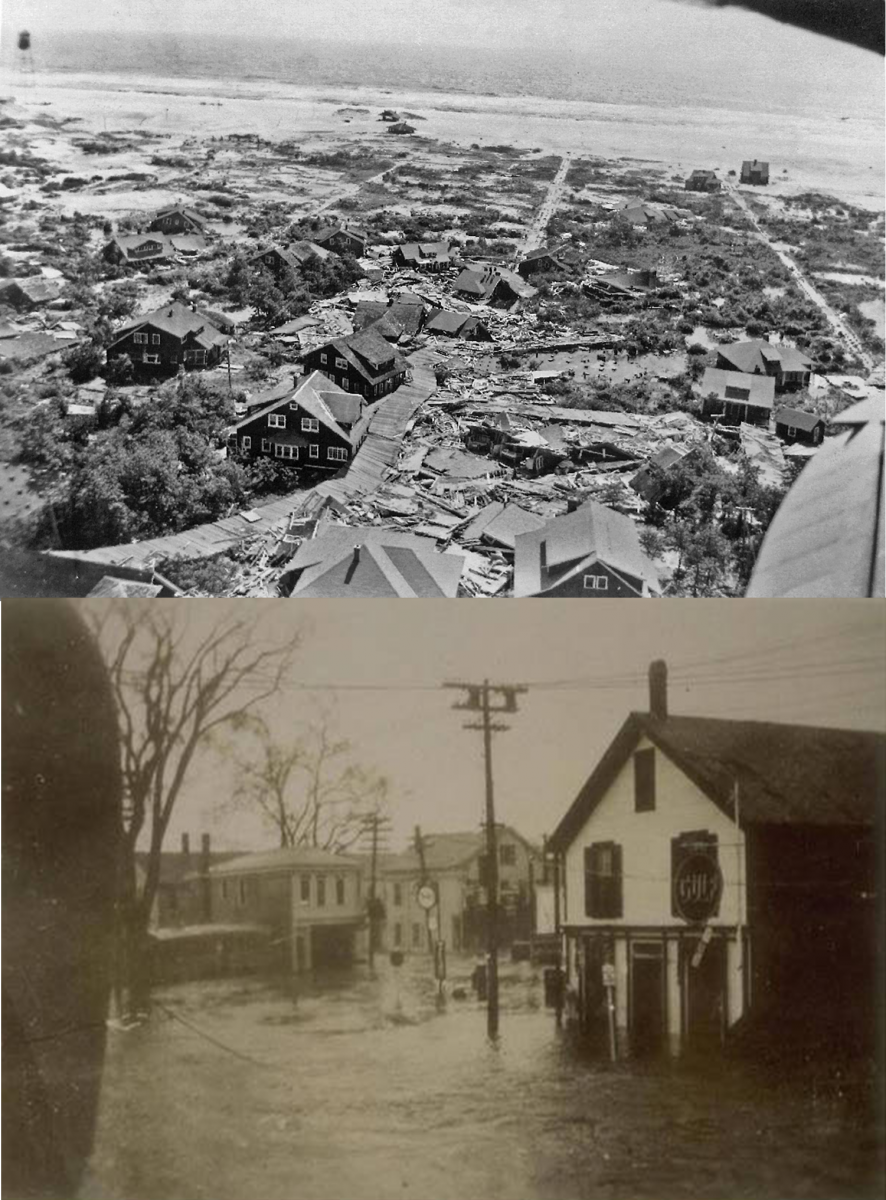

Saltaire, NY flooding damage (top); Mystic, CT flooding damage (bottom)

In Milton, a town south of Boston, the Blue Hill Observatory recorded one of the highest wind gusts in history at an incredible 186 mph. Boston was hit hard and “Old Ironsides” – the historic ship USS Constitution – was torn from its moorings in Boston Navy Yard and suffered slight damage. Hundreds of other ships were not so lucky being completely demolished. The hurricane lost intensity as it passed over northern New England, but was still strong enough to cause widespread damage in Canada later that evening before finally dissipating over southeastern Canada later that night. All told, approximately 682 people were killed by the hurricane, 600 of them in Long Island and southern New England, 9000 homes and buildings were destroyed and 3000 ships were sunk or wrecked. It remains the most powerful and deadliest hurricane in recent New England history, eclipsed in landfall intensity perhaps only by the Great Colonial Hurricane of 1635 - the one storm by which all other storms are still measured to this day.

Final notes on the storm

In terms of weather forecasting for this storm, while the US Weather Bureau did not predict a hurricane landfall, that decision was not without controversy as a junior forecaster named Charlie Pierce believed the storm would curve into Long Island and southern New England due to blocking high pressure to the northeast and trough of low pressure which would guide the storm inland in his opinion. Mr. Pierce was overruled by the chief forecaster, Charles Mitchell. Shortly thereafter, Charles Mitchell resigned and Charlie Pierce was promoted. Video was captured from the actual storm and it can be seen here (courtesy YouTube).

Meteorologist Paul Dorian

Perspecta, Inc.

perspectaweather.com