2:40 PM | *2018 Tropical and Mid-Atlantic Summertime Outlook*

Paul Dorian

Current sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies with La Nina conditions (prevailing in the tropical Pacific Ocean (blue region with colder-than-normal SST); map courtesy NOAA

Executive Summary

• Near normal tropical season in the Atlantic Basin

• La Nina to transition into El Nino in the equatorial Pacific Ocean

• Mixed signals in the Atlantic Basin with colder-than-normal water off of Africa’s west coast and warmer-than-normal in the Gulf of Mexico, Caribbean Sea and western Atlantic Ocean

• US again vulnerable to “home grown” hits

• Analog year comparisons support the notion of a near normal tropical season in the Atlantic Basin

• Analog year comparisons suggest near normal to slightly below-normal temperatures this summer in the Mid-Atlantic region and near normal to slightly above-normal precipitation amounts

Overview

The overall numbers are likely to be near normal this year in terms of the number of tropical storms and hurricanes in the Atlantic Basin (includes the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico). In a normal Atlantic Basin tropical season, there are about 12 named storms with 6 reaching hurricane status and only 2 or 3 actually reaching major status (i.e., category 3, 4 or 5). Last year's tropical season was hyperactive with 17 tropical storms, 10 hurricanes and 6 majors and it followed an above-normal year in 2016. The major factors involved with this year’s tropical outlook include the likely transition of La Nina in the equatorial Pacific Ocean to El Nino conditions by later this summer. The Atlantic Ocean is sending mixed signals in terms of the prospects for tropical activity this season with some sections featuring (unfavorable) colder-than-normal sea surface temperatures and others featuring (favorable) warmer-than-normal waters. The sea surface temperature pattern in the Caribbean Sea, Gulf of Mexico and western Atlantic Ocean makes the southern and eastern US somewhat vulnerable to what I like to call “home-grown” tropical hits during this upcoming tropical season.

Top ten list for strongest continental US hurricane landfalls since 1851 as measured by central pressure at the time of the landfall. Credit Philip Klotzbach, Colorado State University

Weak La Nina Transitions to Weak El Nino

What goes on in the tropical Pacific Ocean does indeed have an effect on the tropical Atlantic Ocean. El Nino, which refers to warmer-than-normal waters in the equatorial Pacific Ocean, affects global weather patterns and it tends to produce faster-than-usual high-altitude winds over the tropical Atlantic Ocean. This El Nino-induced increase in upper atmospheric winds over the tropical Atlantic Ocean is usually an inhibiting factor for tropical storm formation or intensification in the Atlantic Basin as it tends to “rip apart” developing storms. Currently, there are weak La Nina conditions (colder-than-normal) in the equatorial Pacific Ocean; however, signs point to a transition to weak El Nino conditions by later this summer.

Compilation of computer model forecasts for El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO) state for the rest of 2018 with most predicting a transition from La Nina (below zero) to El Nino (above zero) in coming months; map courtesy International Research Institute/CPC, NOAA, ECMWF

Numerous computer forecast models support the idea that weak El Nino conditions should prevail by later this summer in the tropical Pacific Ocean. I do not believe, however, that there will be a moderate-to-strong El Nino this summer and certainly nothing like the strong El Nino of 2015/2016. This scenario of a transition over the next few months would be somewhat neutral for awhile, but then more likely unfavorable for tropical storm formation or intensification if indeed El Nino forms later this summer.

2006 was chosen by me as a top analog year as the sea surface temperature anomaly pattern was quite similar to this year with La Nina conditions prevailing in the tropical Pacific Ocean in April of 2006; map courtesy NOAA

Mixed signals in the Atlantic Basin

The main breeding grounds for Atlantic Ocean tropical systems are in the region between the west coast of Africa and the western Atlantic Ocean and there are mixed signals in terms of sea surface temperatures along this route. Sea surface temperatures of ~85°F are generally considered a requirement for the formation of tropical storms; therefore, above-normal sea surface temperatures are typically quite favorable for tropical storm formation and intensification in the summer tropical season as waves trek westward in the trade winds from Africa’s west coast to the western Atlantic Ocean.

Height anomalies at 500 mb in the June-to-September period of the analog years with nearly normal conditions in the Atlantic Basin; map courtesy NOAA

In recent weeks, however, there has been a persistent pocket of colder-than-normal sea surface temperatures in the eastern Atlantic Ocean near Africa and this would inhibit the formation of tropical storms in that region. On the other hand, the water temperatures are currently generally above-normal in the Caribbean Sea, Gulf of Mexico and much of the western Atlantic Ocean and they have been for many months. These anomalous warm regions should aid in the development and intensification of tropical systems.

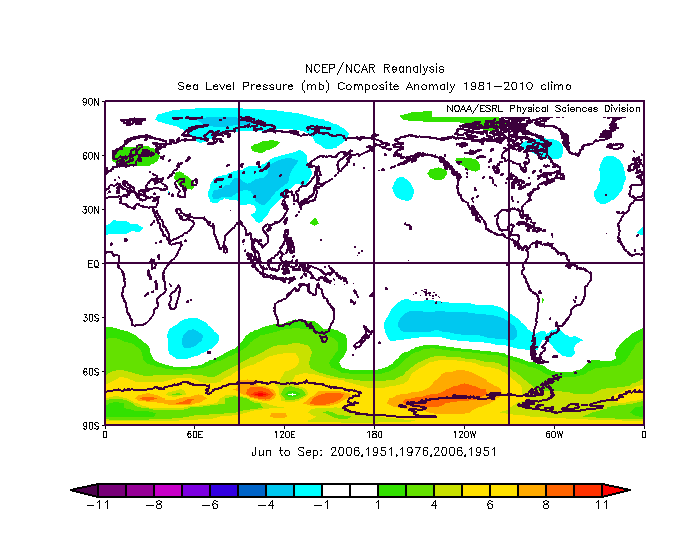

Sea level pressure anomaly in the June-to-September period of the analog years with nearly normal conditions in the Atlantic Basin; map courtesy NOAA

Analog years

Three analog years of 2006, 1951 and 1976 rather closely resemble the current conditions with respect to sea surface temperatures around the world as well as mean geopotential height and sea-level pressure patterns. In fact, these three particular years began with La Nina conditions in the Pacific Ocean that transitioned into El Nino by later in the summer - similar to what is expected this year. In these analog years, the tropical seasons in the Atlantic Basin were fairly close-to-normal with the specific results listed below and the average is based on a “double-weighting” of 2006 and 1951 which I believe are the closest analogs to this year:

2006: 10 storms/5 hurricanes/2 majors

2006: 10 storms/5 hurricanes/2 majors

1951: 12 storms/8 hurricanes/3 majors

1951: 12 storms/8 hurricanes/3 majors

1976: 10 storms/6 hurricanes/2 majors

------------------------------------------------------

Average: 10.8 storms/6.4 hurricanes/2.4 majors

Soil moisture is in pretty decent shape in the eastern US thanks to recent rains and a cold spring which limits evaporation; courtesy NOAA

Mid-Atlantic Outlook

As far as the Mid-Atlantic region is concerned for this summer, I believe there is little chance for an excessively hot summer with any kind of serious drought. One important factor that should inhibit the chances for an excessively hot summer with serious drought conditions is the fact that soil moisture is fairly high around here thanks to recent soaking rainfall events and a cold spring which limits evaporation and there is no reason for that to change dramatically in upcoming days.

Analog year comparisons suggest near normal to slightly below-normal temperatures this summer in the Mid-Atlantic region and near normal to slightly above-normal precipitation amounts; courtesy NOAA

In terms of temperatures, analog year comparisons suggest it could turn out to be in the normal-to-slightly below-normal range. In terms of rainfall for the Mid-Atlantic region, analog comparisons suggest near normal-to-slightly above normal rainfall amounts.

Meteorologist Paul Dorian

Vencore, Inc.

vencoreweather.com