12:10 PM | *Several inhibiting factors for tropical activity in the Atlantic Basin, but don’t let your guard down*

Paul Dorian

This image product is created by differencing the 12.0 and 10.8 µm infrared channels on the Meteosat satellite. The algorithm is sensitive to the presence of dry and/or dusty air in the lower to middle levels of the atmosphere (~600-850 hPa or ~4,500-1,500 m) and is denoted by the yellow to red shading. This image product is useful for monitoring the position and movement of dry air masses such as the Saharan Air Layer (SAL) and mid-latitude dry air intrusions. Credit University of Wisconsin/CIMMS, NOAA

Overview

The Atlantic Basin has been relatively quiet in recent days in terms of tropical activity and it continues to look like this will be a less active tropical season compared to 2017. One of the main factors that led us to an outlook for a less active tropical season back in the springtime was the large patch of colder-than-normal water at that time in the eastern Atlantic Ocean. This continues to exist and is quite likely an inhibiting factor for the formation or intensification of tropical activity in the tropical Atlantic and there are a couple other factors as well that are likely deterring activity. First, Saharan Desert (dry) air has persistently flowed westward from western Africa and into the tropical Atlantic and there are signs that this general pattern will continue into at least the near future. In addition, wind shear has been quite prominent across the tropical Atlantic in recent days and there are reasons to believe that this will continue to impede tropical activity in coming weeks. Don’t let your guard down; however, as all it takes is a direct hit by one storm to make it a memorable tropical season.

Inhibiting Factors

1) Saharan Desert air

A massive plume of Saharan dust appears currently across the tropical North Atlantic Ocean in the latest image product provided by University of Wisconsin/CIMMS (above). Known as the Saharan Air Layer, this dry, dusty air mass forms over the Sahara Desert during late spring, summer and early fall, and typically moves westward over the tropical Atlantic Ocean every three to five days. The Saharan Air Layer extends between 5,000 and 20,000 feet in the atmosphere. When winds are especially strong, the dust can be transported several thousand miles, reaching as far as the Caribbean, Florida and the U.S. Gulf Coast. The dry air associated with the Saharan Air Layer often suppresses hurricane and tropical storm development. Large quantities of dust entering the Atlantic during the summer hurricane season create a stable layer of dry, sinking air, which prevents storms from spinning up or gaining strength. Each year, over one hundred million tons of Saharan dust gets blown across the Atlantic, some of it reaching as far as the Amazon River Basin. The minerals in the dust replenish nutrients in rain forest soils, which are continually depleted by drenching, tropical rains.

North Atlantic sea surface temperature anomalies feature colder-than-normal conditions near Greenland/Iceland and in the "breeding" grounds region of the tropical Atlantic between the west coast of Africa and the Caribbean Sea; Courtesy NOAA, tropicaltidbits.com

2) Colder-than-normal water

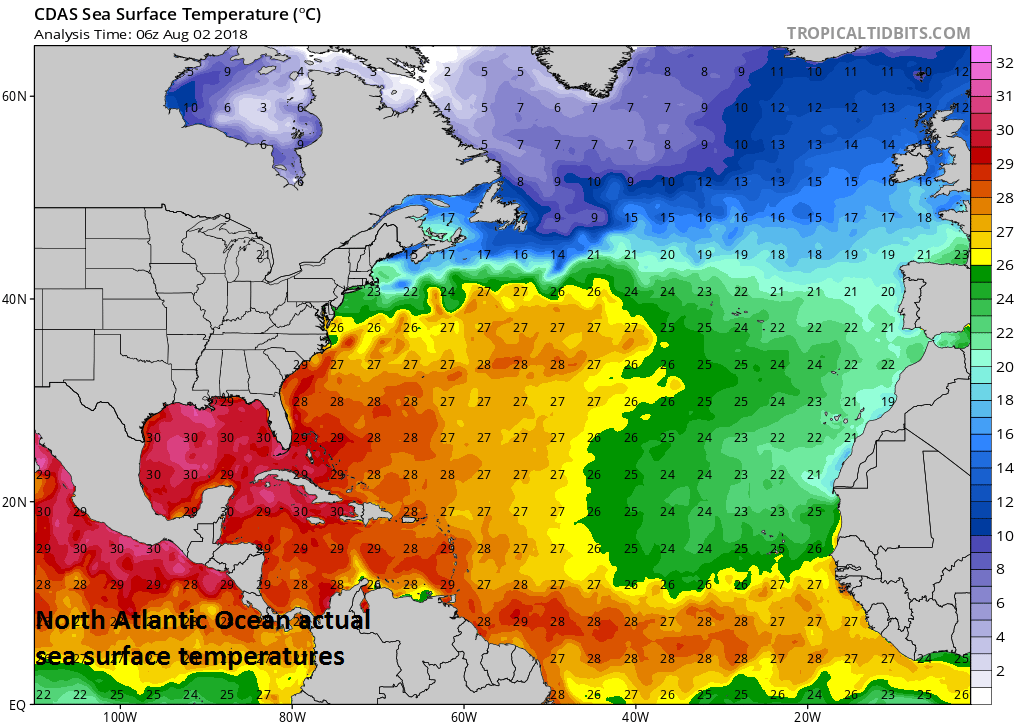

One of the most amazing stories in the world of weather and climate in recent weeks has been the dramatic cool down in the North Atlantic. Tropical Atlantic sea surface temperatures (SSTs) (10-20°N, 60-20°W), averaged over last ten days of July, were the coldest on record since NOAA daily SSTs became available in 1982 (source: Philip Klotzbach, Colorado State University. Empirical observations suggest tropical storm formation in the Atlantic Basin generally requires sea surface temperatures of around 26°C or higher and the below-normal water temperatures off of Africa’s west coast is very likely acting to suppress overall activity with respect to "African-waves". While colder-than-normal water has been rather persistent since the early spring off the west coast of Africa, it has not been until more recently that water temperatures have turned noticeably lower in the area surrounding the southern half of Greenland.

North Atlantic actual sea surface temperatures featuring the warmest waters in the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea; Courtesy NOAA, tropicaltidbits.com

3) Wind Shear

Wind shear refers to any change in wind speed or direction over a short distance within the atmosphere and it is an important factor in controlling tropical storm formation and intensification. In the case of tropical storms, wind shear is important primarily in the vertical direction from the surface to the top of the troposphere. Tropical storms are “heat engines” powered by the release of latent heat when water vapor condenses into liquid water and wind shear suppresses development by removing the heat and moisture needed from near their center. Wind shear will tend to distort the shape of a tropical storm by blowing away the top portion from the lower portion and the resultant tilted vortex is usually a less efficient heat engine.

The latest computer model forecast (NOAA CFSv2) of bulk wind shear indicates it’ll remain rather high in much of the tropical Atlantic and Caribbean Sea during the August/September/October time period. This is a reasonable forecast, in my opinion, based on the idea that an El Nino (warmer-than-normal water) is likely to form by the fall in the equatorial part of the Pacific Ocean and that usually results in increased wind shear in the tropical Atlantic which, in turn, inhibits tropical storm formation and intensification.

NOAA's CFSv2 forecast map of bulk wind shear for the August/September/October time period with highest predicted levels across the Caribbean Sea and tropical Atlantic. A general rule of thumb is that the shear must be 20 knots or less for intensification to occur. Most instances of rapid intensification of hurricanes occur when the wind shear is 10 knots or less. Courtesy NOAA, tropicaltidbits.com, wunderground.com

Final Thoughts

While there are inhibiting factors for tropical storm activity in the Atlantic Basin going forward, it is no time to let your guard down; especially, if your located in the eastern or southern US. Sea surface temperatures are actually above-normal in the Gulf of Mexico and in much of the western Atlantic and the forecast of bulk wind shear in August/September/October is quite low in these same areas – both favorable factors for tropical activity. As a result, odds for what I call a “home-grown” type of tropical system – one that forms near the eastern or southern US coastline and not off of Africa's west coast – are not at all insignificant even though the overall Atlantic Basin season may turn out to be less active than last year. One final note, while the tropical activity in the Atlantic Basin may turn out to be somewhat subdued compared to 2017, the Pacific Ocean is likely to experience a very active season and more active than last year as its sea surface temperatures are warmer-than-normal in many areas.

Meteorologist Paul Dorian

Perspecta, Inc.

perspectaweather.com